Cultures vary immensely as do their internal sub-cultures. For those in an out-group, things might always seem strange. And, for some who expect to understand unconventional norms quickly, it can be daunting (or even frustrating) when one’s acculturation is slower than expected.

For me, understanding Brazilian culture (specifically the aspects that involve cisgender gay men) is still a journey. I am constantly being introduced to themes, jokes, language, and figures by a man whose relationship with me is also something different interculturally to describe.

(Photo credits by PintsizedPioneer)

When it comes to gay Brazilian culture, I have become acquainted with many of its features as of now. There are many familiarities, but also stark contrasts between what I am used in Vancouver, Canada. And, for those who have entered into relationships with Brazilians before, perhaps gotten to know the culture, or are more advanced in Portuguese, this post might resonate in intimate ways.

The following sorts of topics take both time and exposure to Brazilian influences like media to pick up and realise. Some explicit explanation also helps to really understand them. (And, what I describe below should not be considered totally comprehensive either.)

Guess Who is Coming to Jantar?

Let’s discuss dating first …

Dating norms are also different between straight couples in Brazil compared to those in Canada or the US. The popular Greengo (see gringo) Dictionary on Instagram explains some common terminology that might be confusing for foreigners out of context in many Brazilian settings.

Its glossary of relationships is especially informative. Even by South American standards, Brazilians have a lot more ways to define their dating lives and partners.

For many young adults, they might not actually be dating-dating someone, but rather ficando com alguém. The dictionary describes it as ‘occasionally going out,’ but the word itself means ‘staying’ in Portuguese. Ficar is a really versatile verb and is sometimes used for ‘to be’ for temporary descriptions even. Given the distance and our commitment to each other, Thomas and I, who I visited even in Blumenau, settled on this category to best describe our meaningful, but casual ongoing relationship.

Ficando sério entails exclusivity between partners as well as any other category that is more intimate than it. Knowing these levels is helpful in accessing one’s relationship in both gay and straight relationships in Brazil and with Brazilians; and, using these terms with a Brazilian partner can demonstrate a better understanding of the culturally different relationship norms and standards or any confusion between them.

For example, it would be inappropriate to call someone with whom I was only ficando as mozão ‘lit. big love’. This term, as described by Thomas, is for star-crossed lovers akin to Romeo and Juliet level partners. However, other phrases like cadê minhas flor? ‘where are my flowers?’ is totally acceptable, especially because it comes from a meme.

Instagram is King!

An overarching feature of Brazilian culture is a national love of the internet.

The importance of the internet is not just within the LGBT+ community. Most businesses in Brazil need to keep an updated and alluring Instagram to be successful.

YouTube, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter are huge in Brazil. Notoriety/ infamy on the internet is something that Brazilians will reference heavily in vernacular speech (and even aspire to sometimes). And, gay Brazilians (and particularly Black Brazilians) contribute heavily into this, for lack of a better term, “online discourse”.

Many inside jokes exist within the LGBT+ community through these platforms like Instagram.

For example, since the advent of selfies, men from the area of Santa Cecília (in São Paulo) in particular have gained a following for their beautifully pristine, aged wood flooring and often abundance of house plants. Therefore, the Gays de Santa Cecília are now a meme, and many consider them to have the idealised gay lifestyle in São Paulo (particularly in these attractive apartments). The neighbourhood itself is so popular that news outlets have even reporting it has been “[causing] jealousy on social media.”

Politics & Drag

Given Brazil’s historical religiosity and (sadly) contemporary government, the queer community is not generally considered mainstream yet.

In general, views of the current government are negative, centring around criticism of Jair Bolsonaro, the reigning president of Brazil, whose policies have been considered fascist for their ant-Indigenous, anti-LGBT+, anti-education, and anti-healthcare stances. Queer Brazilians are especially vocal in their disdain for the current president/Pocketnaro (a joke name for him).

However, queer artists are held up highly by the people including the sultry gay Silva, funky queen Ludmilla, and of course, Pabllo Vittar (the most famous Brazilian drag queen). These artists are popular in almost every demographic, mixing traditional styles of music like pagode (a form of samba) with updated imagery in videos, modern lyrics, and beats.

In particular, the art of drag and RuPaul’s Drag Race have major followings in Brazil, especially within the queer community, despite recent criticism of the show. I do not know what it is about the art form and series that make them so popular here.

The ability to monitor and keep up to date with queens online probably is a component, as fans follow their favourites with fervour. Online fights are known to happen in massive Facebook groups, some with over 114,000 people. And, commentary in these groups can be thesis-level analysis.

(Photo credits by PintsizedPioneer)

Thomas also clued me into different running jokes that Brazilians have of the series including a general, national confusion of why Ross Matthews is considered funny at all, how RuPaul is secretly an android, and feuds between rival stans. There is also acknowledgement of the disproportionately lower amount of love/fandom shown toward the Black Queens of the series versus their counterparts. This conversation is taken seriously in increasing amounts of circles in Canada and the US too.

Getting to know DragRace fandom through a whole different cultural lens was not something I expected to happen in 2020. Also, watching Drag Race in Portuguese, one will definitely realise that the subtitles use many, many colloquialisms.

And, this observation reflects another important aspect of gay Brazilian culture: language.

Words Matter

It can always be difficult to transition into using a L2 language in more diverse settings (ie like discussing drag, which means knowing some jargon). For this reason, it is always best to learn language in context.

Still, transitioning into gay Brazilian Portuguese was not (and is still not) an easy feat for me.

Slang can be tough to acquire as well as knowing when it is appropriate and how to use it.

(Photo credits by PintsizedPioneer; creator of meme is unknown)

Words like bicha and marica(s) might be thrown around, which have not always been good terms to call gay men in Brazil. They still are not, but between other gay men, they can be commonly used. It is not so different in English today, especially in certain social groups with ‘fag(got)’, ‘bitch’, and even ‘queer’ for some who still consider it unfitting.

However, as a newcomer, it is even more important to know when it is acceptable to use terms like these (if ever) and that they are originally derogatory. Saying the wrong thing and NOT KNOWING you are saying the wrong thing can be disastrous.

Another tendency that might confuse Portuguese learners is that gay men often use the feminine gender declension for male-presenting people amongst other things in speech. Like other Romance languages, Portuguese has grammatical gender, denoted as masculine and feminine. (Romanian actually has neuter too!). So, at bar or between friends, gay men might use the general -a/ -as endings to describe other (gay) men. This usage is also not atypical in English; we call each other queens! But, for foreign listeners, it might be confusing at first. Like, who is the ela in the conversation of just men?

In referring to themselves, queer and gay Brazilians might also use the word – poc. In a North American context, POC usually stands for ‘Person of Colour’. However, in Brazil, it means anyone who identifies as queer. The term actually comes from the sound that drag queens’ heels make in clubs – poc poc – like click clack in English.

A more recent term is yag, which is a synonym for poc today.

(Photo credits by PintsizedPioneer)

And, it took me longer than it should have (as a linguist) to realise that yag is just the word ‘gay’ spelled backwards.

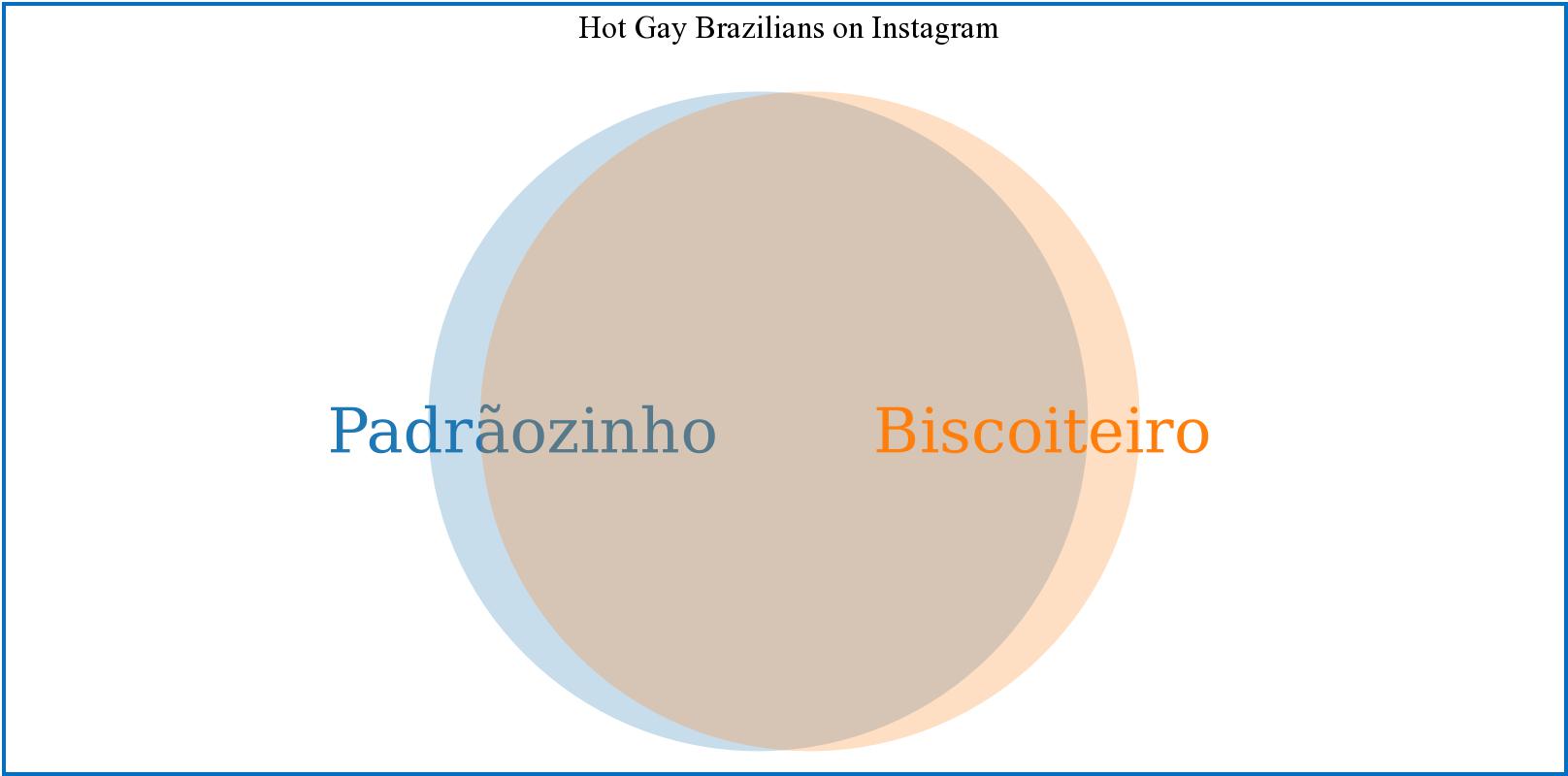

As one can see, there is this delicate balance that gay Brazilian culture and Brazilians in general have with femininity as a whole. Machismo also exists in this part of Latin America, so presenting as masculine does have overt prestige overall in most settings. This cultural preference is visible in the padrão-obsessed corners and envy of Brazil, which includes many gay men.

Remember padrão? Or rather, padrãozinhos?

Where – is – the – Body?

Translated literally as ‘little basics,’ these are the men (not all gay) who have 8-pack abs, go to the gym every day, it seems only really have friends who look like them, and tend to not wear that much clothing. They may also post on Instagram and have tons of followers; however, these social media-minded individuals could also be biscoiteiros who do not necessarily have to possess the same amount of muscle by definition.

Fret not. Although the padrão/biscoiteiro aesthetics are often considered ideal, they are by no means the standard in Brazil or even universally desired there – or anywhere. I may not have had to explicitly state this fact, but it is important to internalise and remember, especially if you are struggling with your own body image (like I sometimes do).

And, Brazilians actually poke fun at these personas all the time too. The ability to name and understand these categories as more so lifestyles than inherent qualities I think plays a large part into this humour.

People acknowledge that looking like a marble statue 24/7 is not realistic for most.

(Photo credits by PintsizedPioneer)

Furthermore, cosmetic plastic surgery is popular in Brazil, which can explain some qualities of these aforementioned individuals. In particular, having a nice smile is a prized feature that has existed as such in Brazil historically. This desirable quality has been maintained through just societal norms and later strategic advertisements. Unsurprisingly, dentistry is a huge cash cow in the country.

These norms are by no means indicators that Brazilians are more negatively superficial than any other group. Let me be clear on that. In fact, plastic surgery in South Korea is an even bigger market there.

However, this topic is good to familiarise oneself with as it can come up more casually in Brazilian conversation than in (I would say) most Canadian or American discussions. There is less stigma about getting a little work done.

The Good, Bad, and Racist

It should also be no shock that these beauty standards overall also reflect the racial dynamics that exist in this colonial country.

Branqueamento or ‘whiting’ in English was a national policy in post-emancipation Brazil. This desire to ‘whiten’ its citizenry included intense immigration campaigns from Europe as well as societal encouragement to marry lighter-skinned individuals to produce even lighter-skinned children and so on.

It was a hugely racist perception and strategy that still permeates much of South America (and other regions) that results in implicit/explicit colourism and overt acts of racism today still.

(Photo credits by Thomas, the Cancer ♋️)

The famous painting A Redenção de Cam is a telling piece that shows the branqueamento mindset clearly at the time of its creation in the late 1800s. It shows the stages of discolouration and celebration of this fact through a family. Brocos y Gómez, the artist of this piece, was a Eugenist himself and supportive of branqueamento; for this reason, I will not visibly share his work on this post.

Applying an understanding of this sad, but real phenomenon to some of Brazil’s beauty standards and who exactly is revered for possessing them today better cues one into their historic origins. And, it helps explain some of the present.

The most recent season of Big Brother Brazil (abbreviated BBB online) was a microcosm of these existing racial tensions and dynamics and how they manifest on a national stage. One participant, a light-skinned man who caught a large gay following online (due to his appearance) was heavily criticised later for his treatment of women and minorities on the show (ie his housemates).

Not Just Carnival!

As one can see, Brazil does not just show its colours during its favourite holiday. Carnival is not the only time that queer Brazilians can express themselves and make some noise.

Queer Brazilians have used the internet, Portuguese language, and warming national acceptance to carve their own space into the cultural landscape of Brazil. Many of Brazilian culture’s features reflect its history for better and for worse with much social change occurring today to try to write past wrongs.

The growing support of LGBT+ lifestyles is just one such expression of change. There are still grave inequalities that find themselves being anti-Black and anti-Indigenous in much of Brazilian culture. However, correction of these tendencies is coming slowly from within as well.

There is so much more I want to enjoy and learn about gay Brazil. Hopefully, I will have more opportunities to travel down there to experience it firsthand. For now, I will have to settle for TINAR and the many, many memes shared with me for now.

We are officially caught up with Brazil posts! Thank goodness. Unfortunately, now, I am in the dilemma facing many travel bloggers. How do you write about travel when it is impossible to do so? Sigh. We will find a way. Safety is the priority … Stay tuned and travel (when possible)!